History and Art at the United States Post Office, Stoneham, MA by Marina Memmo

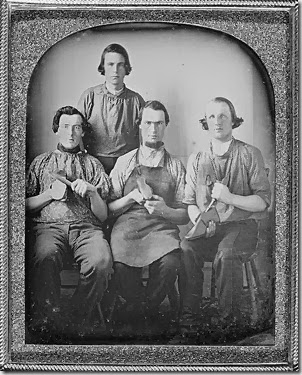

What do the United States Post Office in Stoneham, Massachusetts and Radio City Music Hall have in common? The answer lies above the Post Master’s door. Next time you are waiting in line to mail a letter or package, take a moment to examine the wall sculpture hanging there. It depicts three men diligently working away constructing shoes. Around them are the tools of their trade: knives, awls, lasting hammers, thread, leather, wooden lasts, pincers, stirrups and lapstones.

If you have an eye for art, you might recognize the style of the artist, William Zorach, whose work is also on display in the lobby of Radio City Music Hall in New York City (see Spirit of the Dance, 1932).

The Man and His Art

William Zorach (1887 – 1996) was one of the most talented American artists of the 20th century. His sculptures and watercolors are featured in many museums across the nation [2]; including The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Metropolitan Museum of Fine Art and The National Gallery. In 1998, he was honored as one of America’s finest artists in the White House’s 7th Exhibit on Twentieth-Century American Sculpture.

While most of his work resides in public and private collections, Spirit of the Dance, Spirit of the Sea (a fountain in Bath, Maine), and many others can be seen in public places. At least four, including the Shoemakers of Stoneham, were commissioned by the Federal Government’s Section of Fine Arts for display in United States Post Office buildings.

Zorach’s forms are characterized by a simplicity that is reminiscent of ancient times. His depiction of a Puma (1948), resembles those of Bastet, the Egyptian cat goddess and protector, as she is portrayed in classical Egyptian sculpture dating back to 600 BC. Like the artists of antiquity, Zorach depicts the cat sitting up, alert and watchful. Its limbs, however, are relaxed and its tail curls casually around its body, evoking a sense of calm power.

This sense of inner calm is characteristic of Zorach’s art, but it does not appear to have characterized Zorach himself. In a 1940 newspaper article, he is described as “leaping” and “racing” and “wildly waving his tools in the air”, while his wife Marguerite, who was herself an artist, is described as being “as calm and reserved as her husband is moody”. [3] It seems that the “inner” Marguerite served as Zorach’s model, regardless of the outer form his sculptures took. For more than 50 years, the two were inseparable. Their life-long partnership not only had a profound impact on 20th-century art, but is also a testament to their love and respect for one another [4].

In 1931, William Zorach won the Art Institute of Chicago’s Logan Prize for his sculpture “Mother and Child”. In his autobiography, Art is My Life (1967), he writes this about the piece,“… through the rhythmic relationships of the various units, I feel I have created a living flow of forms — similar to what one might attain in the dance — and fused it into a permanent and solid rock pulsating with an inner life” (p. 86).

In the Shoemakers of Stoneham, Zorach captures this same sense of rhythmic flow between the three figures in the sculpture. Each man works independently on a different part of a shoe, yet together they function as a perfectly balanced and synchronized unit. Zorach’s intentions behind the piece are described by Carolyn Fiske Todd, a Stoneham native who was acquainted with William Zorach and admired his work:“He told me, when we were first introduced, and he learned that I came from Stoneham, that shoemaking by hand was practically an extinct art. He found a little shoemaker in a basement shop in New York, who specialized in hand-made orthopedic shoes. He sat in the traditional manner… It was this body motion that fascinated Bill, and he caught some of the fluidity in his fresco. There is a rhythmic relationship amongst the three figures, even though each works independently. He said he studied the shoemaker for weeks, making sketches, retaining some positions, discarding others, until he felt he could truly reconstruct figures symbolic of a shoe-making town.” – Carolyn Fiske Todd [5]

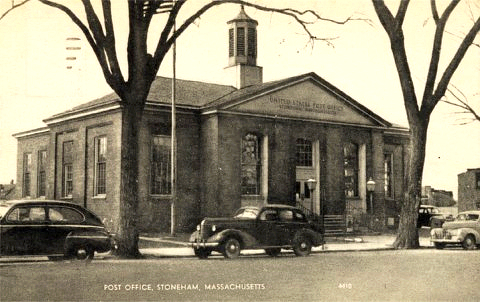

The Stoneham Post Office

The Section of Fine Arts was created as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal program. However, it differed from artwork supported by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), in that artists were chosen based on talent rather than economic need. Established in 1934, “the Section” was administered by the Procurement Division of the Treasury which was responsible for the decoration of public buildings. For a nation struggling to emerge from the depths of the Great Depression, it was hoped that providing public access to fine art would help raise the spirit of the nation. Post offices were prime locations for the project, but not every town had their own post office building. In Stoneham, the post office had been operating out of the Chase Block since 1915. By the 1940s, it was time it had its own building.

When the town decided to construct a building dedicated exclusively to postal service, the Federal Government agreed to pay half the cost of construction, provided that one percent of the budget for the building would be devoted to decorative elements. This included marble counters, hanging lamps, and the commissioning of a work of fine art to hang above the Post Master’s door.

The Gerry House was located on the site of the present-day Post Office prior to 1941. The site chosen for the new building was next door to the Stoneham Savings Bank, at the corner of Hersham and Main Streets, where the Gerry House stood. Prior to the construction of the bank building in 1927, the entire area was part of the Gerry Estate. However, by the 1940s the corner lot had been sold to the bank, and the house itself was largely shut down and falling into disrepair. The last owner agreed to sell the property to the town and in the spring of 1941, the building was demolished to make way for the new post office building.

To be considered for a commission, Zorach would have had to submit a design for evaluation to a panel of jurors, which generally included other artists, the local Post Master, the building’s architect, and a prominent local citizen. In most cases, inspirational designs that featured local themes were preferred. The artist was encouraged to consider the community as his or her patron and often went to great lengths to create works that featured local heroes, industry, history, or other community-specific themes. [7].

In selecting a theme for the new Post Office in Stoneham, William Zorach chose to celebrate the skilled artisans of Stoneham’s pre-industrial past. The three shoemakers depicted in the wall sculpture above the Post Master’s door hearken back to a time when shoes were handmade by skilled craftsmen called cordwainers.

As far back as the 18th century, Stoneham was known as a town where many cordwainers lived and worked. The title itself carried prestige. Cordwainers were respected citizens, who operated their own independent shops and often trained apprentices in the craft [8]. Often, these shops would be located in extensions, called ells, built onto the side of the shoemaker’s home, or nearby in small buildings called “ten-footers” due to their compact dimensions. As an artist who understood what it meant to create something with his own hands, it is not surprising that William Zorach found the Shoemakers of Stoneham to be a highly appealing subject.

Notes:[1] Marina Memmo, Photographer. Used with the permission of the United States Postal Service®. All rights reserved.[2] For a complete list visit: http://www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/zorach_william.html[3] Arnold, E. (1940, May 22). Wife of William Zorach, herself and artist, helps calm him after outbursts. The Pittsburgh Press, p. 21.[4] Nicoll, Jessica (2001). To be modern: The origins of Marguerite and William Zorach’s creative partnership, 1911-1922, in Harmonies and Contrasts: The art of Marguerite and William Zorach, Portland Museum of Art. [5] Todd, C.F. (c. 1974). Letter to Helen Kingsley. Stoneham Historical Society Manuscripts.[6] Walt Sanders, photographer, 1 photographic print: b&w; 33 x 28 cm. Courtesy of the Forbes Watson papers, 1900-1950, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution[7] Raynor, P. (1997). Off the Wall: New Deal Post Office Murals. Enroute, 6(4), Oct-Dec.[8] Visit The Honorable Cordwainer’s Company for more about the history and art of shoemaking.